With work from over 350 poets across 24 countries, the project hopes to elevate the African voice in arts and culture.

The first-ever African poetry archive is rewriting history and doing something that’s never been done before: collecting all of the continent’s vast and diverse writings into one corner of the Internet.

The first-ever African poetry archive is rewriting history and doing something that’s never been done before: collecting all of the continent’s vast and diverse writings into one corner of the Internet.

The Badilisha Poetry X-Change, a project launched in 2012 by the Africa Centre, an arts and culture organization in Cape Town, South Africa, has archived the work of more than 350 poets in 24 countries across the continent and features a a searchable website, mobile app and a weekly podcast.

“Badilisha was conceived to prioritize poetic African voices and ensure that Africans have the option of being inspired and influenced by their own poets,”said Linda Kaoma, Badilisha’s project manager.

As Kaoma points out, despite the continent’s enormous population, only 2 percent of the world’s published books are by African authors. The archive hopes to change that—it organizes poets by name, country, language, and theme, and includes a photo, biography, and sound file of the poet reading his or her work in both the poet’s original language and in English. The archive now includes poems written in 14 different languages.

“If you look at Europe, it’s very easy to find archives of many things, but in Africa, because a lot of history and culture was passed down by the oral tradition and there was lack of documentation, that’s not possible,” said Kaoma shortly after the launch. “We didn’t want history to repeat itself.”

Indeed, thanks to colonialism, much of the continent’s homegrown literary culture has been splintered. As a result, there was never a comprehensive archive of African poetry—and no easy way for many Africans to access the treasure troves of their own culture—until now.

As the project points out on its website, without access to such an archive, “many Africans are not inspired or influenced by their own writers and poets—negatively impacting their personal growth, identity, development, and sense of place.”

What’s more, the perception that the world has of Africa has been largely formed by outsiders looking in, or from African writers writing for the West.

“We used to spend so much time agonizing over the question of whether we were writing for the West,” the Nigerian author Okey Ndibe has said. “In retrospect, I see our error. In Nigeria, we grew up reading the West. The West was talking to us. Why shouldn’t the West read Nigeria? Why shouldn’t we talk back?”

While there have been successes in that regard, it’s complicated. In the last year or so, African writers have been in vogue in the American publishing world. Last year, 10 percent of those who graduated from the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop had African roots. Still, publishers want marketable books and continue to look for African writers who specifically appeal to Western audiences.

As African writer Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani wrote in The New York Times last year, “All sorts of marvelous things have happened for African literature” in the last decade, from being nominated for prestigious literary awards to being prominently displayed in bookstores. “However, we are telling only the stories that foreigners allow us to tell. Publishers in New York and London decide which of us to offer contracts, which of our stories to present to the world.”

Developing a true African literary canon is tricky, as most African countries don’t publish a lot of books. South Africa, which publishes the most books in Africa, ranks 45 in the number of books published worldwide, according to UNESCO. Nigeria, which publishes the second-largest volume of books in the continent, ranks 63rd in the world.

With the Badilisha Poetry X-Change, the world is getting unfiltered writing straight from Africa, by Africans, about Africa. The mobile app also takes advantage of the fact that most people in Africa use their phones to access the Internet; the poetry shared on the site mimics oral tradition by letting users listen to poetry read to them and also addresses the larger problem of getting poetry published.

“A lot of publishers are not publishing poetry,” Kaoma told The Guardian. “But it does not have to be confined to books. It’s alive. The voice adds texture, adds a different layer to the poems. A lot of people are enjoying listening to poetry rather than reading it.”

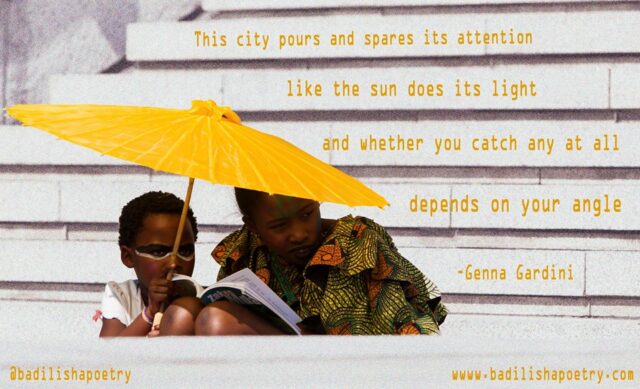

Master storytellers performing during the Badilisha Poetry X-Change “City Desired Tour” in Cape Town.

For Kaoma and the Badilisha project, it’s less about attracting outside audiences than it is about empowering Africans to discover their own voices through culture and history.

“It’s a great place to come and reflect and see what other poets are doing,” Kaoma said. “I think there is value in being influenced by someone in the same context: You don’t have to change yourself to be recognized. You can be African and write about whatever you want to write about.”

A version of this story was originally published here by Take Part. All images are from Badilisha’s Facebook page.