Today is Universal Children’s Day! In honor of kids everywhere, we’re celebrating the winners of the Children’s Africana Book Awards (CABA). This award recognizes authors and illustrators who create accurate, quality children’s books that counter stereotypical depictions of Africa.

Ifeoma Onyefulu with two of her children’s books.

When Ifeoma Onyefulu began writing children’s books, she was motivated by more than just the desire to become a published author.

“My child was young, and I wanted to show him what Nigeria was really like,” said Onyefulu, who now lives in England. “But when I went to look for books, all I could find were safaris and animals. Don’t get me wrong, I love animals. But that’s not all you have in Africa; people live there!”

So Onyefulu began writing, and to date she has penned more than a dozen children’s books inspired by the Nigerian village in which she grew up.

I sat down recently with Onyefulu and six other CABA winners, past and present, to hear in their own words why they think quality children’s books about Africa are so important. Here’s what they had to say:

1. The world is diverse—but kids everywhere have a lot in common.

Two winners of the 2014 Children’s Africana Book Award: Bundle of Secrets: Savita Returns Home by Mubina Hassanali Kirmani and Tony Siema, and Africa is My Home: A Child of the Amistad by Monica Edinger and Robert Byrd. Photo credit: Africa Access

“Often times, Africa is seen as a very homogeneous continent,” said Mubina Hassanali Kirmani, whose book “Bundle of Secrets” is one of this year’s winners.

Kirmani was raised in Mombassa, Kenya, and was surprised to learn later in life how little others elsewhere understood about her country. “There was so much diversity where I was raised, and I felt that message needed to be sent out.”

This desire to portray Africa’s rich diversity was common among the other authors I spoke with, but so was the desire to show that some experiences are universal.

“I think it’s important for children everywhere to see other children playing the same ways and doing the same things,” Onyefulu said. “We are all so similar. You may be Bill Gates’ child, but as soon as you open a box of toys, your kid is going to play with the box, not the toy. It’s things like that—children all over the world do that.”

A.G. Ford won a CABA award this year for illustrating a book by Desmond Tutu. In the story, a South African boy must respond to kids who are calling him mean names. “That’s something everyone deals with,” Ford said. “The setting took place in Africa, but it applies to other places, too.”

2. Stories help children understand and value other cultures.

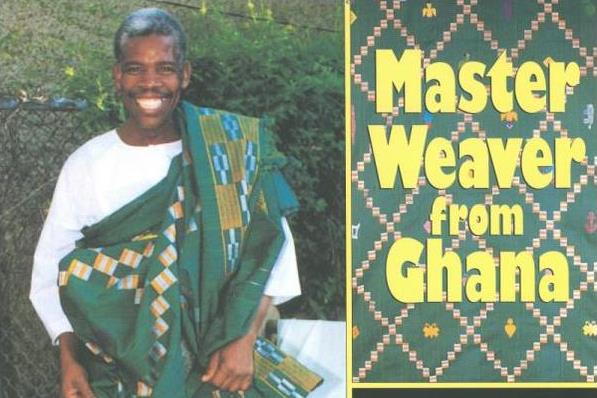

Meyer’s book, Master Weaver from Ghana, allows young readers to explore Ghanaian culture through the eyes of a traditional weaver and his family. Photo Credit: Louise Meyer, Gilbert Ahiagble and Neestor Hernandez.

For their book “Once Upon a Time in Ghana,” Anna Cottrell and Togbi Kumassah teamed up to record and translate the traditional tales of Ghanaian oral storytellers.

“Publishing these stories for a wider audience is a way of saying ‘your stories are worth something, and you are worth something,’” said Cottrell.

“My community’s values—of honesty, hard work, integrity, and forbearance—are all enshrined in those stories,” Kumassah, who is himself an oral storyteller, said. “As society grows, we need to share the stories of the past, or they fade away.”

Louise Meyer, who won a CABA award in 1998 for “The Master Weaver from Ghana,” reiterated how valuable it can be to share a family’s story- and also the importance of getting that story right. “Being honest and true to the facts in children’s books is critical,” she said.

3. Books can fight stereotypes and misinformation at a young age.

Ifeoma Onyefulu (left) is a Nigerian author and winner of two CABA awards. Her book A is for Africa depicts everyday life in Nigeria with stunning photos she took herself. Photo credit: Ifeoma Onyefulu

Monica Edinger, author of “Africa is My Home, A Child of the Amistad,” is a former Peace Corps volunteer who began writing children’s books during Sierra Leone’s Civil War. “Sierra Leone and its people were being represented in the media in this really horrendous way,” Edinger said.

She felt it was important to share stories that showed there was more to Sierra Leone than conflict. “Real stories, about real people, make a big difference. But unfortunately that isn’t the standard narrative in children’s books.”

These authors have seen firsthand the powerful impact a well-told, accurate story can have on Western children who aren’t very familiar with African culture. “You can’t blame a child for believing the wrong images they see of Africa on TV,” Onyefulu said.

“When I go into schools, children ask me why I’m telling them about Africa because their only impression of Africa is that it’s poor,” she said. “After I share African stories, and a child says ‘Oh, I didn’t know Africa was like that’—that, to me, is a big deal.”