In the developed world we rarely walk into a room and think twice before flipping a switch to turn on the lights. We seldom, if ever, consider the possibility that when we go to the doctor’s office it may not have electricity, or give us medicines that haven’t been property refrigerated.

Most mothers in the developed world don’t consider whether or not to give birth in a facility that has electricity. When was the last time you showed up at work on a Monday morning and worried that the lights may not come on? Yet, this is not the case for billions of people around the world.

The International Energy Agency reports that around 19% of the world’s population, or 1.3 billion people around the world have NO access to electricity. In sub-Saharan Africa 7 out of 10 people don’t have access to electricity.

If, as our recent report suggests, Poverty is Sexist, then it also goes that energy poverty is sexist. The most remarkable thing we found in doing research for the Poverty is Sexist report is how little data exists about the number of girls and women living in energy poverty and the ways it impacts their lives.

While there is a lot we don’t know this is what we do know:

– We do know that women in sub-Saharan Africa currently spend up to eight hours per day collecting fuel for cooking and heating their homes, and that cooking over open fires and traditional stoves that use biomass means that these women are breathing in pollutants every day. According to the World Health Organization, this indoor smoke is responsible for half a million annual deaths due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among women worldwide. If these women had access to electricity and clean cooking technology this time could be better spend on income-generating pursuits.

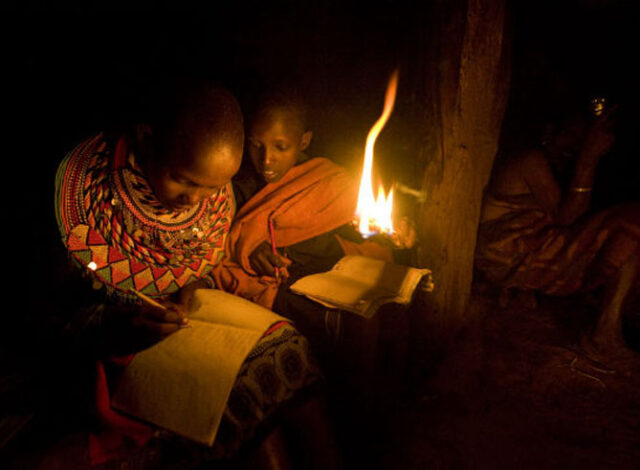

– We do know that 50% of children in the developing world go to primary schools without access to electricity. This affects more than 291 million children worldwide; 90 million of those children live in sub-Saharan Africa. We also know that lack of access to safe and reliable electricity limits the number of hours in the day children are able to study and learn to daylight hours, and frequently girls are unable to attend school because they have to collect fuel for their family fires.

– On the positive side, we know that in a small study in South Africa, women’s employment increased by 9.5% where electricity was provided, most likely because it released women from home production and enabled them to participate in economic pursuits. But we also know that nearly half of African businesses cite lack of access to reliable power as a major hindrance to their growth, so guaranteeing reliable access to electricity is a key ingredient for economic success.

We need to know more. We need better data about how energy poverty directly impacts girls and women. But at the same time we already know enough to know that this is not ok.

There is something we can do about it. The U.S. Congress failed to pass legislation last year that would have provided much needed financing to bring electricity to Africa. There is an opportunity for them to pass it this year, but the bill hasn’t yet been introduced. Now is the time to let Congress know how important you think the Electrify Africa bill is to you.