This piece is part of a reporting partnership between ONE and Refugees Deeply.

Fatuma Omar Ismail currently studies chemical engineering at the University of Toronto in Canada on a scholarship. But she spent most of her childhood in Dadaab, a complex of refugee camps in northern Kenya, near the border with Somalia, where much of her family still resides. Below, she describes the daily challenges she faced as a 12-year-old determined to change her future.

The muezzin calls the second azan of the dawn prayer. You wake up. Your eyelids are heavy with sleep but you can’t afford another minute of it. You get up and open the door made of oil cans, careful not to wake up your younger siblings as you step out of the bedroom.

You immediately feel cold. It is still dark. You pick up the torch from the tree trunk and find your toothbrush. After freshening up, you make your way to the kitchen and light the stove with firewood. You prepare the tea, put it in thermos flask, wash the dishes and sweep the balbalo (a dining room with a matted floor under the canopy of a tree).

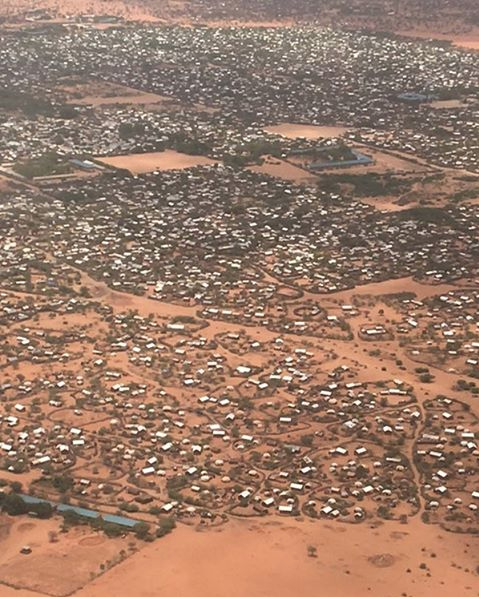

A photo of the Dadaab refugee camp. (Photo credit: Instagram.com/U2)

You ready everything your mother will later need to make breakfast. The rest of the family is up now, except the five smallest siblings who are still too young to pray. You take your ablution, put on your hijab, and pray. You watch as your father and two older brothers head to the mosque. You hear your dad asking them whether they read the morning prayer or not.

Your mum thanks you for setting up the kitchen. You grin. You look at the Casio watch on your wrist. You are only 12 years old, and it is unusual for a girl in this camp to have a watch. The $9 that it cost is a fortune when times are tough and even food is scarce. It reminds you of the sacrifices your parents make for you and your brothers and sisters. It is 5:20 a.m.

You don’t have enough time to memorize the two required pages of Quran. You imagine how furious the maalim (Quranic teacher) will be. You remind yourself that you can’t be expelled. You’ve got to cram it in the next 20 minutes. Thankfully, you do. By 5:45 a.m., as you get ready to go to dugsi (the Quranic school), your younger siblings wake up. Why do they have to wake up now when you are almost late for dugsi? You mutter the complaint to yourself under your breath. You clean and dress them.

Now it’s almost 6 a.m. You say bye to your mother and run to dugsi. On the way, you bump into your father. He smiles and hugs you. He tells you running is not for ladies. But he does so in cheerful way. You smile and say you will keep it in mind.

The Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya. (Photo credit: ONE)

At dugsi you settle in your usual spot and recite the Quran silently. Caasho, your notorious dagaalley (fighter) neighbor hits you as she passes by. Ignore her, you tell yourself.

Amid the noise of children reciting the Quran, you remember your father saying ‘banaankii mare maradiis geed maqabsato’ (whoever walks on a clear road does not get thorns in their clothes). You chuckle at the irony of it. How many times have you been picked on by others while you were minding your own business? And every time you ignore them, but she is still there saying ‘nayaa iisoo bax’ (come fight with me).

The maalim arrives. You concentrate on the Quran. It’s your turn to recite. Thankfully, you do so without making a mistake.

“Masha Allah! Tomorrow, you will recite the next three pages,” the maalim says. Three pages?! Oh no.

The time is now 7 a.m. You run home. Today is Tuesday. You debate whether you should attend madrassa or school. You decide to go to madrassa. You put on the heavy black polyester hijab with its skirt. “What is the point of wearing the skirt when the hijab covers it all?” you ask yourself. But it doesn’t matter. You don’t have enough time. The gates close at 7:30. You make a silent prayer your mum doesn’t give you another chore before you leave. Your prayer is answered. You leave without eating breakfast.

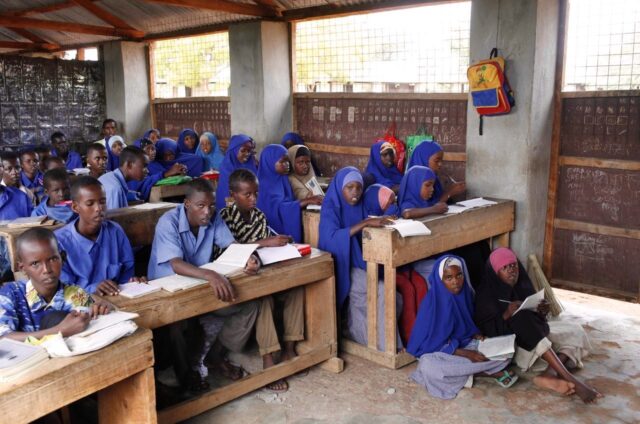

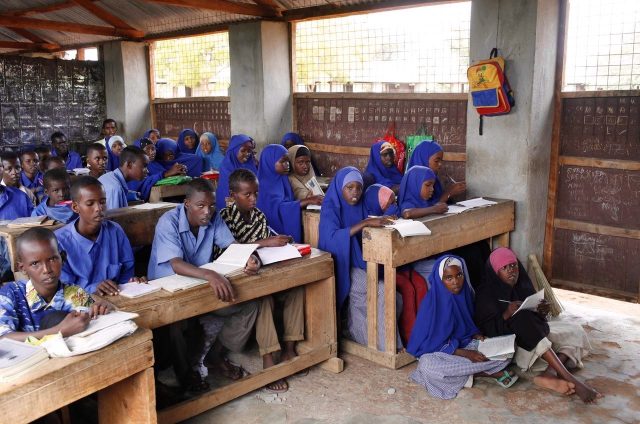

Somali refugees study at the school in the Hagadera camp in Dadaab. (Photo credit: Facelly/Sipa)

By fourth period, you’re hungry and tired. The scorching sun doesn’t help either. You hear the Qiraa (recitation) teacher explaining the difference between idhqam and iqlab. You can’t grasp whatever he is saying. One, two … you count to pass the time. It is 12:30. You head home with your best friend. You chat.

She tells you Caasho, the bully, has been spreading rumors that you’re afraid of her. You chuckle. You think of all the things in your mind – the chores you have waiting for you at home after your afternoon school shift, the lessons you missed this morning, the three pages of Quran you have to memorize before tomorrow, the tafsiir (Quranic translation) you have to attend tonight at the nearby mosque, the tiredness, the heat, the sweat. “Let her,” you tell your friend. You don’t have time or energy to waste on Caasho.

A group of boys are playing football in the nearby field. They start catcalling you. It makes you angry. You should give them a piece of your mind, you think to yourself. You think of your parents. It’s a habit you’ve developed over time – thinking of your parents before you do or say anything. You hear and see their reactions in your mind. “You shouldn’t have said anything to them; af daboolan waa dahab aabe (a closed mouth is golden).”

Too much for a 12-year-old to deal with, you think to yourself. You keep walking and in no time, you are at home. You sigh: The hard part of the day has just begun.

Women in the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya in April 2016. (Photo credit: ONE)

You eat whatever food you can find, pray dhuhr (the midday prayer) and put on your school uniform – a blue hijab and blue and white-striped skirt. The blue hijab feels transparent. You put on another hijab and put the blue one on top. You remember the first lesson in the afternoon is social studies – your favorite subject. The thought makes trekking in the heat bearable. It is not trekking, the school is just few minutes away, there are students coming from far blocks, don’t be ungrateful, you scold yourself – and off you go.

On the way, you think of how lucky you are. You have parents who love you and encourage you to study. You meet Hawo, another neighbor of yours carrying her son to the hospital. She’s not much older than me, you think to yourself. My life will be different, it has to be different. I don’t want to spend the rest of my life here. I will excel in my studies and insh’allah (God willing), it will take me somewhere.

You feel a renewed motivation. You silently pray Allah to be with you and you thank Him for His blessings.

You don’t know when you arrived at your class. It’s 2 in the afternoon now and the first lesson starts. You concentrate like never before, keeping thoughts of the heat and overcrowding from your mind.

***

Fatuma came to international prominence after her outstanding exam results saw her given a rare place at one of Kenya’s best girls schools. Living between Dadaab and Nairobi, she built on the opportunity given to her to earn the right to study abroad. Her story is proof of the importance of girls’ access to education.