Story and photos by Ayodeji Rotinwa.

As the children in Makoko, Nigeria, row canoes across the water, their heads are barely visible from a distance. But they’re not rowing for sport: They’re running errands and selling goods within their sprawling river-based community set in a lagoon in the heart of Lagos.

Slum2School founder Otto Orondaam and some of the Mokoko students.

Originally a small fishing village, Makoko is now estimated to be home to up to 300,000 people, with as many as 10,000 children out of school. The village is a maze of small aluminum and wood structures set on stilts in the water or on wet, spongy land. If you stretch out both hands in one spot, you can touch two homes.

The community does have schools, though. One of them is a rough mass of gray bricks. The roof has caved in and there are no desks or chairs. It’s not a good situation, but if any parents in the community want to send their children to school, this is what they can afford. They pay N30 ($.10) for admission daily.

In 2012, Otto Orondaam was tired of hearing negative news about struggling, out-of-school children. After seeing Makoko from a bridge one evening during one of Lagos’ famous traffic jams, he decided to visit the community — and he kept coming back every week. He resigned from his bank job to start Slum2School Africa, a social development organization that, in its first year, enrolled 118 kids in school.

A Mokoko student draws in a classroom.

When Otto walks around the village, young children wave and cheerfully call out, “Education!” and “Slum2School!” Otto usually waves back and asks, “Why are you not in school today? Go now!”

Slum2School is known for sponsoring disadvantaged kids into school, but it actually does a lot more than that. It’s an entirely volunteer-driven organization with a structure that invests in 360-degree child development.

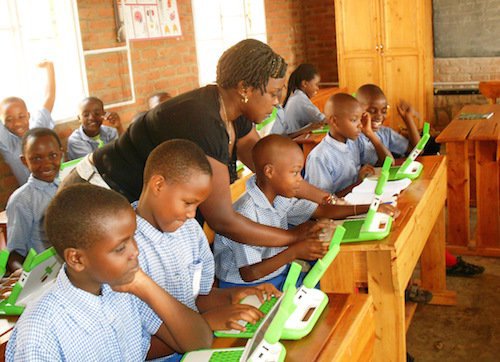

It has more than 40 teams that oversee vigilant mentorship of the children, computer literacy programs, and early childhood development. Teams also teach creative classes and provide guidance and counseling services and medical interventions.

Kids between the ages of 2 and 7 study in the Slum2School Early Development Centre.

The children are provided with medical insurance and their academic performance is monitored and evaluated regularly. The organization also adopts and upgrades schools in Makoko, equipping them with computers, books, and skilled teachers.

“Before Slum2School, I could not be proud of myself,” says 16-year-old Samuel Iroko. “The school I was attending before, I could not read or write because they didn’t teach us well. It was Slum2School that enrolled me in a new school. They provide me with my school needs like a bag, uniform, sandals, and textbook.”

Samuel attended his first school – not unlike the one described earlier – for six years before Slum2School came along. He is now in his first year in Junior Secondary School. He wants to become a doctor someday.

“Slum2School gave me the hope to achieve my dream,” he says. “I want to treat all sick children in our community…” He pauses. “Not only our community. I want to treat all sick children.”

The academic monitoring is performed by Slum2School’s community-based volunteers. These are educated young adults who live in Makoko, usually waiting for their chance at university. Besides wanting to make a difference in lives of their younger siblings or neighbors, these volunteers seek an opportunity to make a difference in their own.

One of the Slum2School volunteer mentors plays with a student.

One such volunteer, Magdalene Seide, 22, is waiting for admission into Lagos State University. But in the meantime, she’s gained critical work experience as an administrator with Slum2School.

“Before Slum2School, I used to be shy,” she says. “But now, whenever we have a meeting, I stand up and talk. I am developing my self-esteem.”

It’s all part of Otto’s vision for a better future: “The success of the organization lies not only in that we are helping children,” he says, “but that it is young people driving this change.”

Over the course of four years, Slum2School has directly enrolled 650 children in schools. Its early childhood development center is open to ages 2 through 7. It launched a Computer Development Centre used by more than 25 schools. The retention rate of enrolled children is 66 percent.

Slum2School students play in their community.

These numbers are somewhat encouraging, but the problem of large numbers of out of school children in Nigeria remains. The northeast has come under an increasingly violent wave of insurgency that has seen children kidnapped by Boko Haram, and schools shut down.

“Our future is threatened,” says Otto. “Let us not look at the statistics as just numbers. Let us remember that each child is a human resource that can boost the economy. Imagine an economy with [more] graduates who are creating jobs, building businesses, starting enterprises… See the opportunity?”