By Chris Kardish, Raimund Zühr, Sabine Campe (SEEK Development)

There are few United Nations goals with a bigger impact across the entire development agenda than education. Improving the health of societies, reducing poverty and inequality, eradicating hunger, empowering women – all of them require giant leaps forward in global education. But as many researchers and advocates have pointed out, getting there will require more investment, including from wealthier donor countries to developing countries.

However, existing data reveals the opposite: donor country funding has actually declined in recent years as a share of overall donor aid to developing countries. Encouraging greater investment requires transparency and an understanding of where things stand now with spending on global education. That’s why the Donor Tracker has turned its attention to education.

The free website offers quick and easy access to quantitative and qualitative information on funding trends, strategic priorities, and decision-making of 14 major OECD donor countries, while also identifying potential opportunities to advocate for more and better funding for development. The Donor Tracker also produces “Deep Dives” on the funding and priorities of those 14 donors in key sectors of development: most recently, a new Deep Dive on education.

The education “Deep Dive” helps illustrate some key trends about international funding for one of the most important sectors of development.

Why has donor support declined?

Bilateral funding for education among donor countries has declined by 4% since its 2010 peak: from US$12.5 billion to US$12 billion, according to UNESCO, all while funding for global development overall increased by 5%.

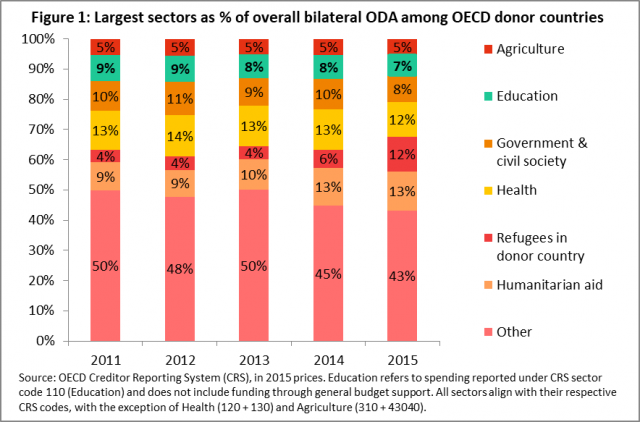

What explains this? One key element is that donor priorities have increasingly shifted funding from regular development assistance programs to humanitarian aid and to increasingly cover the costs of hosting refugees within their own borders, which they can report to the OECD as Official Development Assistance (ODA). The share of the global ODA bucket allocated to humanitarian aid grew from 9% of bilateral ODA in 2011 to 13% in 2015 (Figure 1). The share of bilateral ODA used for covering the costs of hosting refugees has grown dramatically in recent years, from 4% in 2011 to 12% in 2015. Preliminary OECD data for 2016 suggests further increases.

Both trends reflect donor response to the increasing number of ongoing humanitarian crises and conflicts in the world and record levels of forced displacement. More broadly, many donor governments are placing a stronger focus on migration and conflict-related spending. As a result, programs and sectors, including education, must increasingly prove how they contribute to “tackling the root causes” of displacement, or else face funding cuts.

Who are the biggest donor countries?

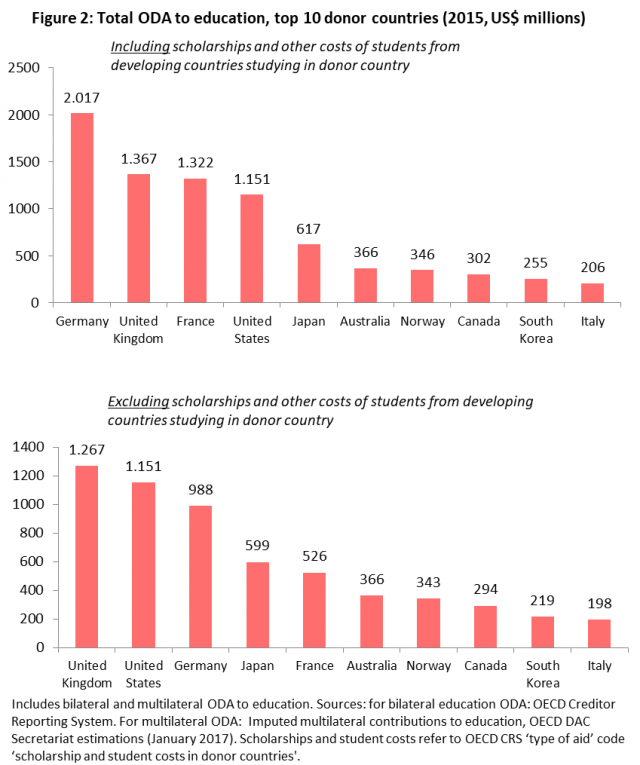

Germany clearly comes out as the largest donor country in absolute size, having spent US$2 billion on education ODA in 2015, according to OECD data (Figure 2), followed by the UK (US$1.4 billion), France (US$1.3 billion), and the United States (US$1.2 billion). However, as many education advocates point out, the OECD data does not give a correct impression of how much donor countries actually spend on education outside of their borders, because they can count as ODA scholarships and other costs of students from developing countries attending their own universities.

For that reason, the Donor Tracker also looks at how a donor’s ranking within the education landscape changes when excluding these costs. This is particularly relevant in the cases of Germany and France: in-country student costs made up around half of their total education ODA in 2015 (France: 60%; Germany: 51%). Excluding these in-country costs, the United Kingdom spends the most on education, followed by the United States, with Germany and France slipping to 3rd and 5th place, respectively.

Which areas of education do country donors fund?

Donor country investments focus on university-level education: on average, 42% of donor countries’ education ODA was allocated to this sector in 2015. This is driven in large part by in-country spending on students from developing countries. In contrast, OECD donor countries allocated only 26% of their bilateral education ODA in 2015 to basic education (which includes primary education, early childhood education, and basic life skills for youth and adults).

This matters because basic education and secondary education are vital to ensuring all countries meet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4, which calls for “inclusive and equitable quality education” for all, and they are both significantly underfunded.