Megan Gieske is a storyteller and photographer based in Cape Town, South Africa.

Under Cape Town Together, communities long-divided over racial lines are uniting to help those in-need.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing financial crisis in South Africa, Mzikhona Mgedle lost his job in the non-profit sector, but he wasn’t backing down. He started the Langa CAN, “community action network,” to meet the specific needs of his community, and he wasn’t alone.

Mzikhona Mgedle is part of a growing movement to meet community needs through self-organization, “for people by the people.” Using the power of social media in a new way, neighborhood-level CANs (“community action networks”) like the Langa CAN, unite the country during a global crisis.

“We move fast with the speed of trust, where we collaborate among ourselves,” Mzikhona said, “We work with anyone who’s willing to be part of the network.”

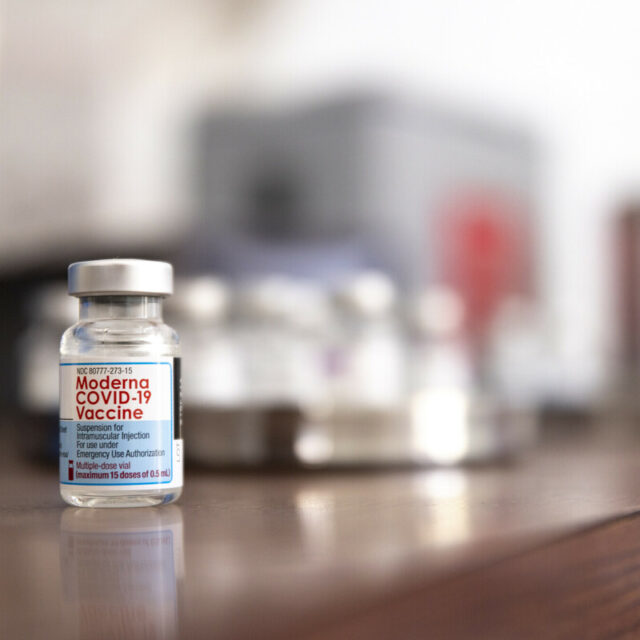

Responding to the pandemic

CANs like Mzikhona’s began as a rapid, community-led response to COVID-19. In just five months, 170 CANs spread across the city, and the Facebook group for their umbrella network, Cape Town Together, grew to over 18,000 members from its start on March 17th.

In a famously divided country, the millions of South Africans living in densely populated townships that are part of the legacy of apartheid or “apartness,” were disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

At the edge of the city, Langa’s tidy, tin-roofed houses lay behind a high fence on the busy road that leads to the Cape Town International Airport. Laundry drapes over sheds covered with tin, plastic sheeting, and scrap wood, or flags in the wind outside crowded, brick apartment buildings. Stretching across 3.09 km2 (1.19 mi2) of flatland, 80,000 people often share one-bedroom homes with multiple families and communal taps with hundreds of neighbors. Commands to “social distance” and “wash hands with soap and water” come with greater difficulty here.

This is the community Mzikhona Mgedle comes from.

Langa CAN began with the distribution of food parcels from Mzikhona’s own home. “Our kitchens have been active ever since three days before the lockdown (beginning on March 27th). Since I initiated the project, now it has established six community kitchens,” Mzikhona said. “Each month, we can feed 9,000 people.”

Helping the community

Twenty-five women volunteer to cook in the community kitchens. Most of the women volunteering lost their jobs due to the lockdown, and yet, they’re feeding 9,000 people a month.

“Instead of staying at home doing nothing, we like to come here and help, and cook for other people, so at least we are doing something good to benefit others,” Nosipho said. Nosipho cooks in a repurposed shipping container with three other women.

“Every day, the number of people queuing goes up, including the kids and the elderly,” Lulu said. She started a community kitchen in her own home with members of her family and her neighborhood.

The women make sure social distancing is practiced, everyone wears their masks, and sanitizes their hands. “You have to have a passion [for] doing this, otherwise you’ll get tired,” Lulu said. Her passion is clear, as is what can happen when women unite to defend their community.

“Most people who are testing positive are breadwinners, people who are providing income to the family,” Mzikohna said, “When they’re in self-quarantine for 14 days in government facilities, kids will starve or won’t get medical care.”

Throughout the pandemic, school feeding schemes closed, leaving children without their one meal a day.

An estimated 3 million people in South Africa lost their jobs between February and April, and recent research shows that the percentage of people who have run out of money for food in the last year has increased from 25% to 47%.

With bicycles donated by Heroes on Bikes, Langa CAN delivers cooked food to the bedridden, elderly or disabled, and people in isolation or those who have COVID-19.

Together with education packs for students, Langa CAN delivers food parcels anonymously to COVID-positive families with the help of a local clinic.

They also equip women from the community with materials and sewing machines to make masks for the elderly and others at high-risk. Doctors and health practitioners design flyers to teach best health practices for COVID-19, and by partnering with other CANs, they provide study materials to schools. They also plan to begin a community garden to grow vegetables for the kitchens.

“We all try to build back better for solidarity, where we gather and discuss what it is we want to achieve,” Mzikhona said.

CANS connecting communities

Although Langa and Claremont are just a 15 minute drive from each other, they’ve historically been separated. Under apartheid, Langa was declared one of the first black-only townships, and Claremont represents one of the predominately white, leafy suburbs flanking the slopes of Table Mountain. Through the use of social media, and apps like Whatsapp and Telegram, the Langa and Claremont CANs could partner, bridging the gaps of some of South Africa’s longest divides. The Claremont CAN fundraises for donations for the community kitchens in Langa.

For Mzikhona, social solidarity spreads faster than COVID-19. “This is a new way of building back better,” Mzikhona said that by developing and building relationships, “We can make sure we fight the divide in Cape Town of racism.”

It’s a beautiful testament to what a long-divided country like South Africa can achieve, when communities unite together under one cause, to fight COVID-19 and its effects of food insecurity and unemployment.