All over the world, lives have been put on hold due to COVID-19, and students have not been spared. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, school closures have interrupted children’s learning since March 2020, when for the first time studies were suspended by order of the President of the Republic. At the beginning of the lockdown, teachers did not know how long it would last. So that studies could continue, pupils were given homework, but the system didn’t work because in the DRC, only a few people have easy access to the tools needed for remote learning, including the internet and reliable electricity.

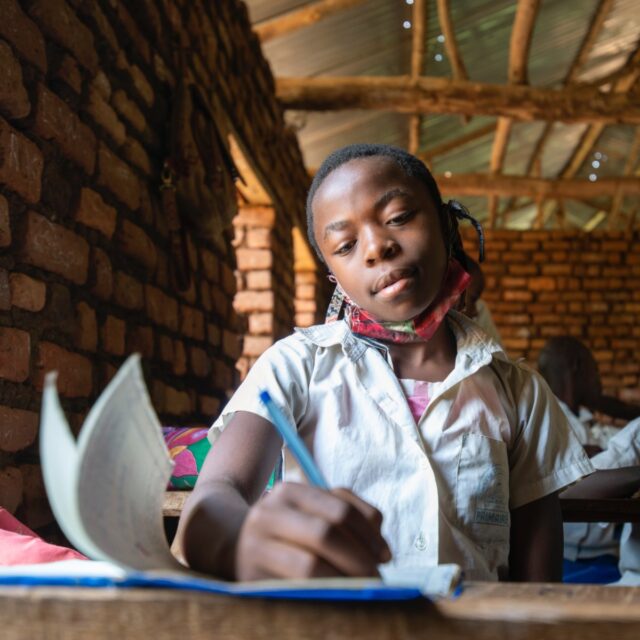

Today, a few months since classes have resumed, the negative impact school closures and accessibility to resources had on children is clear. According to the director of Malinde Primary School (located in the territory of Idjwi Sud in the province of South Kivu in the DRC), Buhuru Ntamwenge Zachée, the attainment level of students in primary school has dropped remarkably as a result of the lockdowns.

“I have personally noticed a decline in pupils’ performance since school activities have started again. For example, in reading lessons when a child arrived in the third year of primary school, they would be able to read an invitation and relay the message to their parents, but now the children find it impossible; even those who are in the fifth year have serious difficulties in reading and writing,” Zachée said. “This makes me unhappy as a headmaster and parent because the future of these children is really at stake.”

Lasting lockdown effects

This feeling is widespread, with students, parents, and school officials all affected by school closures. For children between the ages of 6 and 10, there’s been a significant interruption to their development in reading and writing, including for the children at Malinde.

In some parts of the world, children were able to make the switch to distance learning, but in the DRC it was virtually impossible due to the lack of reliable internet and electricity.

Bahati Bugiri, a 10-year-old student in year 6 at Malinde, shared their experience of learning while in lockdown.

“When the schools were closed because of coronavirus I didn’t feel happy because we couldn’t study at school,” Bahati shared. “Now that I am in school I am very happy, because when I finish my studies I want to be governor of South Kivu.”

Bahati Bugiri, a 10-year-old student in year 6 at Malinde.

But many did not have time to keep up their grades while at home, either because they were playing or because they were busy with other things, as in the case for 13-year-old Nankafu Ndamwenge Furaha.

“When the schools were closed, we worked the land; we looked for wood; we drew water; I spent my days helping at home with household chores,” Nankafu explained. “Now that we have started school again I feel happy that we are able to prepare for the TENAFEP – the exam to finish primary school. In the future, I would like to be a doctor to treat the sick people in my village. That’s why I would ask the government not to close the schools again, because when you close the schools there is no education, and without education I will never be able to be a doctor.”

If the schools are closed again it could be a real catastrophe for many children, especially those living in rural areas where there is no option to study online. It is vital to stay safe from COVID-19, as health comes first, but education is also essential because it is the same children who are at school today who will be able to lead this country in the future.

“As for coronavirus, we cannot run away from it but rather we must fight it. We ask the government to better protect children in school. We cannot pay for thermometers to take their temperatures, or for hand sanitizer for each class. As for wearing masks, many parents find it difficult to pay for two or three masks for their children. If the government can help us with masks it would really help us – since we declared free education in primary schools, we have all full classes and we even have classes with 70 pupils. But we can’t manage to control them all because it’s difficult to respect social distancing,” headmaster Zachée says on what leaders can do to help.

“The government could help to facilitate education with the construction of more classrooms so that we can double the number of classes available, and help get education back on track.”

How you can make a difference

School closures and the challenges of remote learning due to the pandemic have greatly impacted children’s education globally. Prior to the pandemic, 90% of 10-year-olds in low-income countries couldn’t read or understand something simple, like a heath leaflet or school test. Now, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, that number is at risk of increasing, with the potential for girls, in particular, to fall through the cracks. That’s why we must act now — and you can help.

As world leaders meet to come up with a global response to the learning crisis, join us in asking them to invest in quality education for all children, regardless of where they live. Because the children of today, are the leaders, doctors, and scientists of tomorrow.