In September 2020, Vanessa and her husband, both residents of rural Makueni County in Kenya, reported to the FSD FinMark Trust COVID tracker, a survey of economic and social issue across seven African countries, that the couple had not gotten any work for three months, and the family was running out of food. Like Vanessa and her family, many respondents to the COVID tracker drew down their savings, asked for remittances, and borrowed from friends to survive the pandemic. About 13% opted to sell their assets to meet basic family needs.

The pandemic’s economic impacts have been significant in Kenya, with marked effects on remittances, fuel prices, access to affordable food, and the ways in which ordinary Kenyans access money.

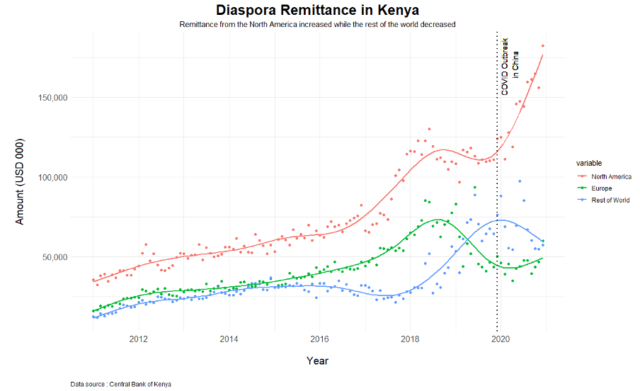

As the pandemic ravaged economies around the world, Kenyans living abroad sent back US$3 billion in 2020 — the highest amount ever recorded. Families with relations in North America managed to cope better during the pandemic. But others, especially people living in low-income communities, had to rely on the government and development partners’ cash transfer programs. A survey in September by Financial Sector Deepening (FSD) revealed that only 1.9% of Kenyans have received cash relief from the government. A further 24% of the population received support from other agencies — leaving many Kenyans with no or unknown financial coping mechanisms.

Unintended consequence

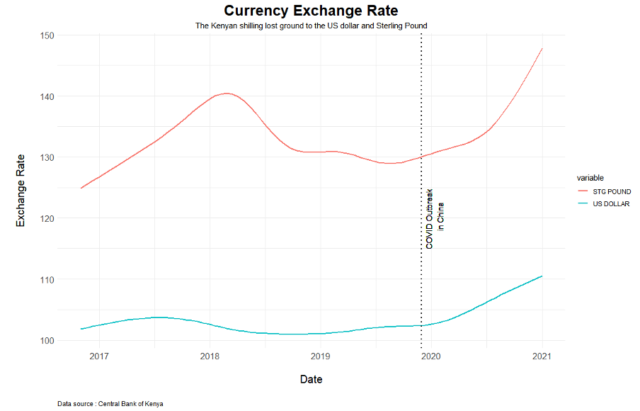

Since 2017, foreign remittances surpassed tea and coffee to become Kenya’s top foreign exchange earner. As a consequence of the increase in remittances, the exchange rate of the US dollar and British pound against the Kenyan shilling depreciated by 10%. At the start of 2020, the Kenyan shilling was exchanging at Kshs 101.4 against the US dollar but depreciated to close the year at Kshs 111.68.

The weakness of the shilling led to the largest jump in fuel prices (11%) in Kenya in more than 13 years. Fuel has been one of the major imports in the country and it is estimated that 70% of the urban poor rely on kerosene for lighting and as a source of energy. In addition, transportation costs shot up due to increase in pump prices and the government’s directive to limit capacity in public transportation to 60% in order to enforce social distancing. As a result, people who rely on public transportation to travel to work and carry goods to their businesses, experienced a further squeeze on their wallets — and 2021 doesn’t look any better.

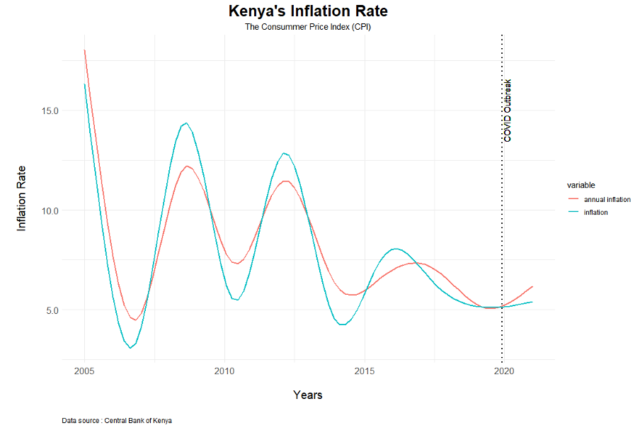

The inflation rate, however, remained low and stable in the country. The prices of food and non-alcoholic drinks, which make up one-third of the inflation basket, increased only marginally, by 0.8%, due to good rainfall and a decrease in demand during COVID-19. A swarm of desert locusts invaded northern Kenya early in 2020, but did not cause significant destruction to food crops, thankfully preserving a good supply of food. The increase in fuel prices in 2020, however, led to a 13% increase in transportation costs.That a growing number of Kenyans are going hungry during the crisis is likely driven by declining incomes rather than food price inflation.

Mobile money

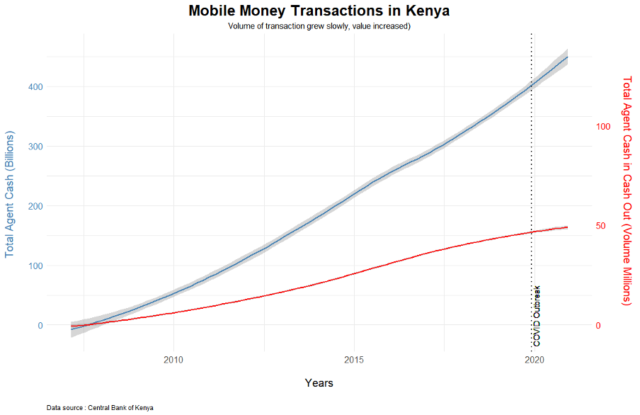

In Kenya, mobile money has been rightfully lauded for providing financial inclusion, and the government’s cash relief programme is disbursed to mobile wallets. In March 2020, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) took measures to facilitate increased use of mobile money transactions, including charging no fees for transactions below Kshs 1,000 and lifting the daily limit of mobile money transactions from Kshs 150,000 to Kshs 300,000.

These measures seem to have been mostly utilized by middle- to high-income earners in Kenya The volume of transactions undertaken on mobile money increased marginally after the CBK intervention while the value of transactions continued its trend of exponential growth.

Digital loans also provide much needed relief for low-income earners and led to an increase in the number of transactions undertaken via mobile phones. Emmanuel, a resident of a rural area in coastal Kenya, reported to FSD that he had to borrow Kshs 12,000 (US$120) from a savings group he runs with his friends to pay an M-Shwari loan (a mobile loan service offered on MPESA). He then reborrowed Kshs 15,000 (US$150) to repay the group in order to ensure he doesn’t lose his most reliable source of credit.

During this pandemic, the most vulnerable have been hit hardest by the economic impacts of COVID-19. We must ensure world leaders are using every tool to support those hardest hit.